The two articles, juxtaposed on the newspaper’s front page, couldn’t be more divergent. “Mars rover landing: NASA’s Perseverance touches down safely in search of life” details the arrival on Mars of “the most advanced astrobiology laboratory ever sent to another world.” The article presents the Perseverance mission as an inspirational story of human ingenuity, of reaching if not quite for the stars, at least to the embrace of a planetary neighbour. By contrast, “Human destruction of nature is ‘senseless and suicidal’, warns UN chief” provides yet another warning of how the ever-escalating damage we’ve inflicted on our own planet imperils the future of humankind.

Reading the two articles together produces head-splitting cognitive dissonance, two competing narratives that seem impossible to reconcile. Our current pandemic circumstances seem to produce ever-more of these discomfiting, “time is out of joint” realizations that our world is seriously off-kilter and potentially spiralling towards a very bleak future.

I struggle to balance the “to Infinity . . . and Beyond” optimism of the Perseverance mission with the pessimism that stems from the increasing scientific evidence that we are engineering what could well be our demise as a species. How can one dream of the stars when here on Earth the Four Horsemen are galloping ever-closer?

I believe in science. Indeed, my discipline, Political Science, is among the very few physical and social sciences that claim “science” as part of their names. I also identify strongly with noted political scientist E. H. Carr’s dictum that “Political Science is the science not only of what is, but of what ought to be.”¹ I’m thus torn between awe for the remarkable quest for scientific knowledge and a disturbing moral sense that the human and financial resources that brought Perseverance to a Martian crater might have been better directed to more pressing Earth-bound problems – of which there is a number almost as infinite as the stars in the sky.

According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the overall budget for the Perseverance mission is some $US 3 billion. This pales in comparison to the $CAN 340 billion in pandemic-related support payments made by the Canadian federal government in the first eight months of 2020, and is but a tiny fraction of the Biden Administration’s recently approved $1.9 trillion economic stimulus plan. Alternatively, the total cost of the Perseverance mission approximates the amount of money Google makes in a mere six days, what Americans spend on their pets every 10 days, or Disney’s global box office revenue for its universe-shattering Avengers: Endgame.

In addition to NASA’s Perseverance, the United Arab Emirates’ Hope orbiter recently began its examination of the Martian atmosphere, with particular focus on changes in the planet’s climate. The Chinese Tianwen-1 (“Questioning the Heavens”) mission is expected to land a rover on the surface of Mars later this spring. Each of these missions will provide new scientific insight into the history of the Red Planet, including potential answers as to whether Mars may have once supported life.

While such knowledge has its own inherent value, I wonder how much, if anything, it will add to our understanding of Earthly climate change. Does science not already tell us that rapid climate change and its manifold impacts threaten not only all aspects of Earth’s biosphere, but imperils the very future of humankind? Is it possible to undertake a meaningful cost-benefit analysis to justify these interplanetary endeavours?

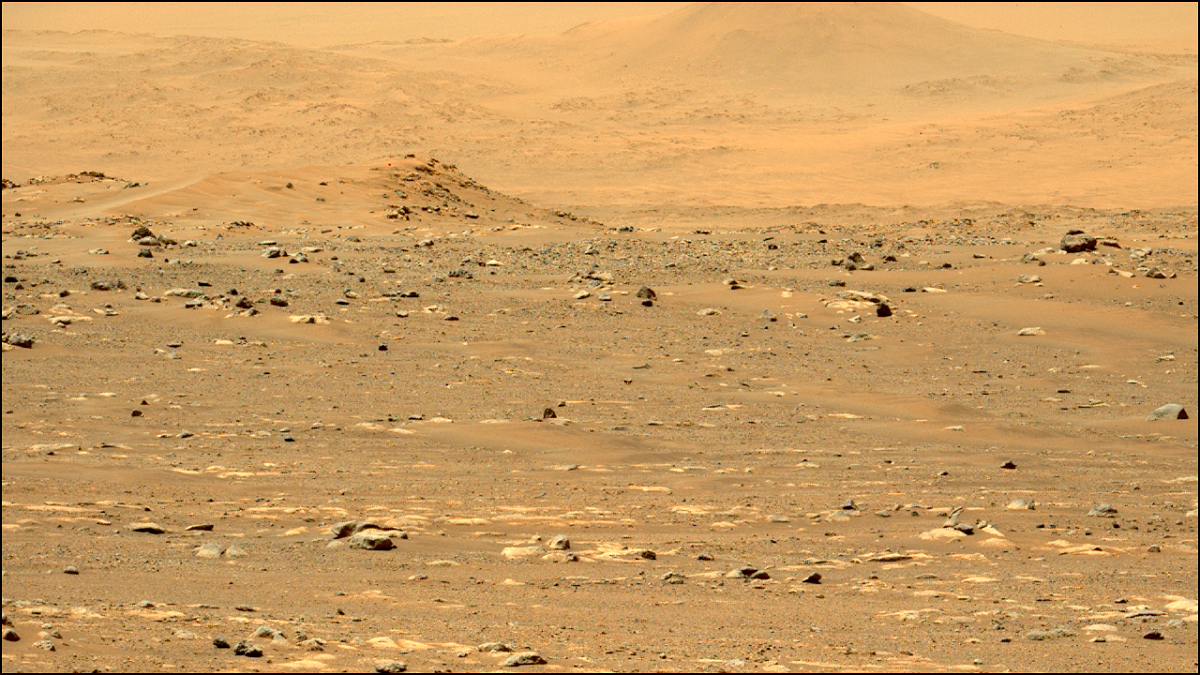

Although I thrill to Perseverance’s panoramic views of another world and marvel at the science that brings me the sound of the Martian wind, I can’t help feeling deeply conflicted. Faced with such great challenges on our home planet, reaching towards Mars or even further beyond seems nothing short of hubristic, if not orbiting dangerously close to the Biblical edict, “Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall.” And in addition to such moral quandaries, the romantic in me decries the human spoilation of yet another heavenly realm. The human-made tracks on the Martian surface are indelible.

As I struggle with these contortions of divergent thought, I am drawn to David Bowie’s 1973 “Life on Mars?” Although the song’s refrain seems to have little, or nothing, to do with the actual planet, Bowie’s celebrated anthem suggests a frustrated yearning for something better. In a 1997 interview Bowie indicated that the song presents a sensitive young girl “disappointed with reality . . . that though she’s living in the doldrums of reality she’s being told that there’s a far greater life somewhere, and she’s bitterly disappointed that she doesn’t have access to it.” Bowie’s abstract, even surreal lyrics, together with the song’s slightly other-worldly melody, capture perfectly for me the strange dissonance that today brings Earth and its neighbouring world into an unsettling new alignment.

¹ Carr, E. H. The twenty years’ crisis, 1919-1935: an introduction to the study of international relations. London: Macmillan, 1939. p.5.