Usually when we talk about connectivity in cities, we’re talking about human transportation. But it’s not just humans who need to move around the city. Just as we use transit networks to get to where we live, work and play, wildlife need to be able to move to where they feed, breed and winter.

Parks are important for wildlife in the city, but few can support wildlife long term. Either they aren’t large enough to support an entire population, or they are lacking variety in their types of habitat, forcing individuals to move somewhere else to find food or a mate.

Knowing the best places for wildlife to move around the city, understanding what the local ‘wildlife transit network’ looks like, can help future planning. By mapping out the network, we can highlight areas that need to be protected from development, as well as identify places where restoration would help rebuild connections.

So, what does Halifax’s ‘wildlife transit network’ look like?

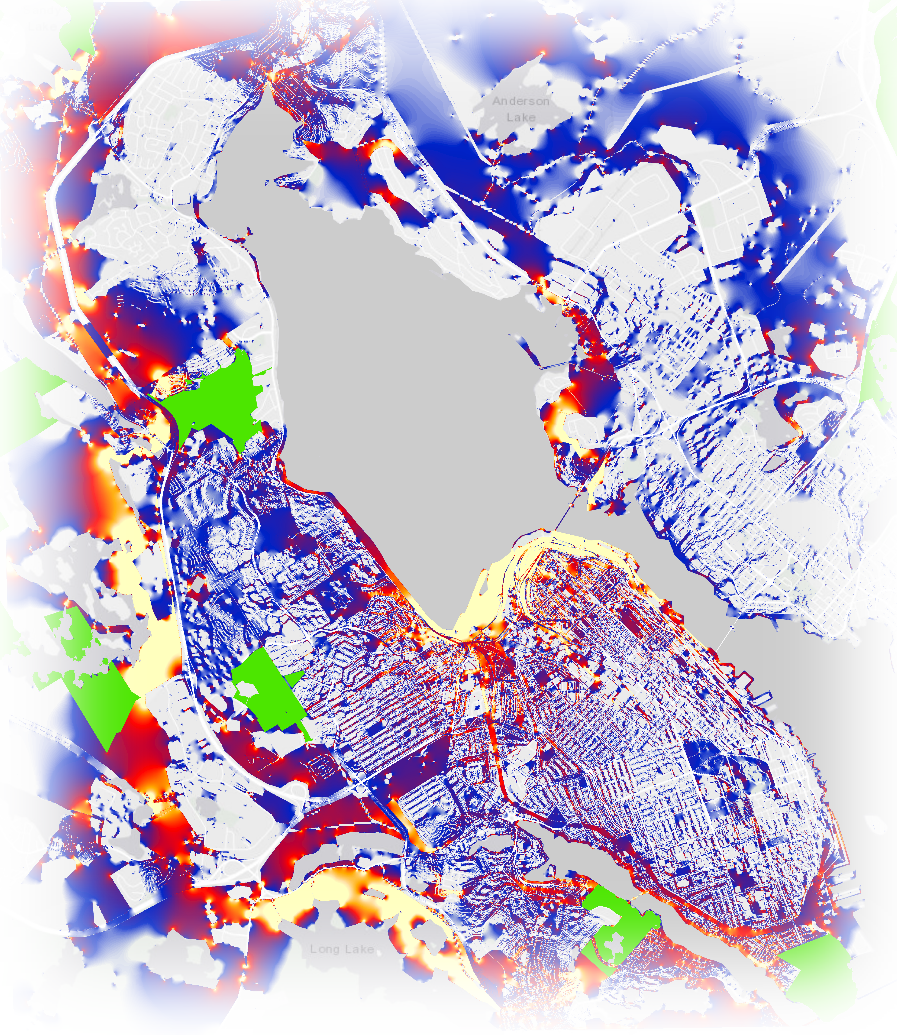

To figure it out, I started by using a tool called Circuitscape to map the connectedness of greenspace in Halifax’s urban core:

In this map, coloured areas are those that have at least some potential for wildlife movement, as there is some greenspace that is at least somewhat connected to more greenspace. But if we are interested in building a wildlife transit network, the red-yellow areas are really important to pay attention to. These are areas where there is high potential for wildlife movement, but it’s restricted to narrow corridors, like along a rail corridor or a narrow patch of forest between subdivisions. They are the key linkages between parks (shown in green on the map) and form the backbone of our wildlife transit network.

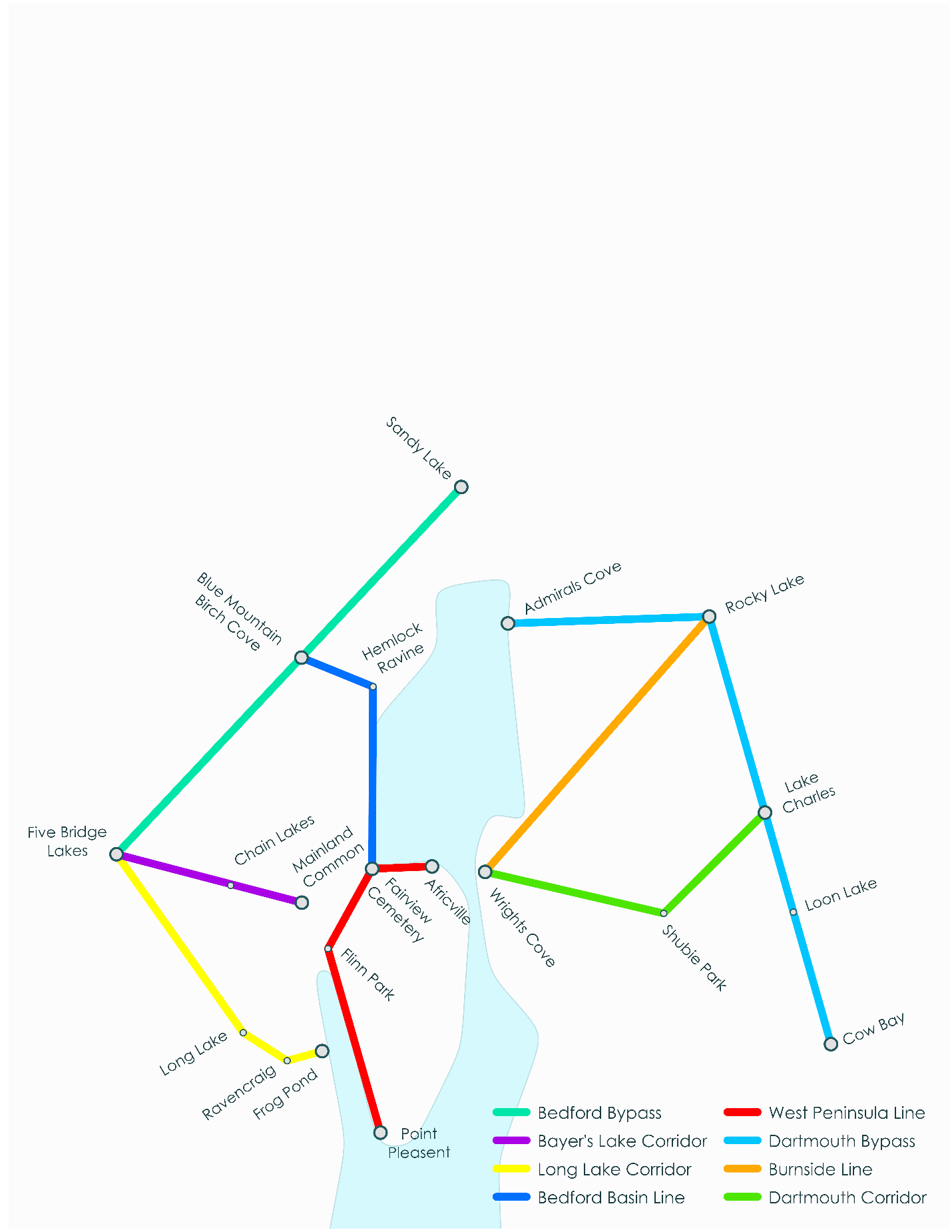

I simplified this map to design a network of parks and other relatively-non developed areas, connected by the best corridors we have to think about how wildlife move around Halifax:

It’s important to understand that this network isn’t like a subway system. It doesn’t always represent clear paths for wildlife follow, but it does give us a good idea of where wildlife movement could occur and can help us identify where efforts to help wildlife movement, like building wildlife crossings across roads, would be the most beneficial.

While parks get a lot of attention regarding city wildlife, it’s important that we think beyond them and consider the whole network. A transit network wouldn’t be any good if it were just a bunch of stations with no way to get between them. Similarly, a system of parks is most useful to wildlife when it’s all connected.

Photo by Nirav Jadeja on Unsplash