When you think of a farm, what do you picture? Wheat fields? A dairy farm? Chicken barns?

What about a fish farm?

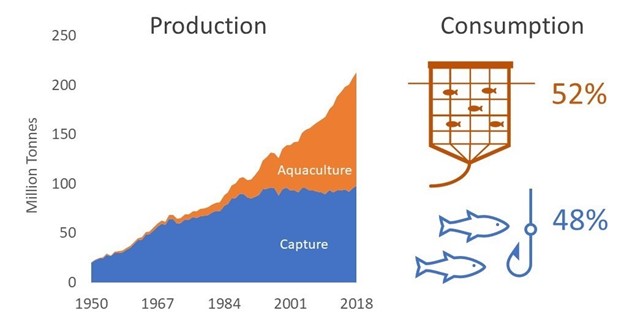

We’re eating more seafood than ever before, and it’s not just because there are more of us on the planet. Since the mid-twentieth century, seafood consumption has grown at twice the rate of population growth and faster than the rate of consumption of all other animal protein. Seafood comes from both fisheries and aquaculture, but while fisheries growth has slowed in recent years, aquaculture growth continues to climb. In fact, over half of the seafood available for human consumption now comes from aquaculture.

Left: Growth in farmed and wild caught seafood production 1950-2018. Data from FAO. 2020. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics. Global production by production source 1950-2018 (FishstatJ). In: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department [online]. Rome. Updated 2020. Right: Percentage of seafood available for human consumption that comes from aquaculture and capture fisheries.

This period of rapid growth in aquaculture production has been referred to as the “blue revolution”, analogous to the “green revolution”, which took place in the mid-twentieth century when new technology allowed for a rapid increased in agricultural production. But unlike the green revolution, the blue revolution is still ongoing; aquaculture is growing faster than any other food system in the world.

So, with a growing population and increased demand for animal-based protein, is aquaculture the future of food?

The feeding strategies of the different species we farm is one aspect of aquaculture that is important to the sustainability of the blue revolution. Some aquaculture species like mussels and oysters filter nutrients from the water, while other species like salmon, shrimp, and tilapia require the addition of food by the farmer. Production of fed aquaculture has grown faster than unfed aquaculture, accounting for approximately 70% of production in tonnes in 2018.

Fed species accounted for 69.5% of aquaculture production in 2018.

The use of wild fish in fish feed was once considered a major limitation to the future of aquaculture; after all, there is only so much fish to go around. However, a recent article published in Nature highlighting many of the changes in aquaculture that have occurred over the past 20 years of the blue revolution provides an update on feed efficiency and composition. Although the production of fed fish has tripled since the year 2000, landings of fish used to make fish feed has declined.

Reliance on wild fish for aquaculture feed has declined for several reasons, one of which is increasing use of land-based plant ingredients in fish feed. For example, canola and soy are taking the place of fish oil and fishmeal in fish feed.

But transition to terrestrial feed ingredients leads to another limitation for the future of aquaculture; feed production now competes for land use with crop production for other animal feed, human consumption, the production of biofuels, and animal grazing. Still, a global human diet that relies on a larger proportion of farmed fish is expected to use less land and fewer land-based crops than one that relies on more land-based animal protein as it takes less feed to produce a pound of fish than a pound of chicken or beef. While reducing reliance on wild fish ingredients is desirable there are also environmental concerns associated with land-based ingredients such as the conversion of rainforests to cropland used to produce soy.

Fish feed is expensive, especially marine ingredients like fish oil and fishmeal. The authors of the recent aquaculture retrospective point to cost savings as the motivation to improve feed efficiency and reduce reliance on wild fish ingredients in the aquaculture industry, a motivation that was reinforced by private regulation like eco-certification. For example, some eco-certifiers set limits on the quantity of wild fish used to produce cultured fish. Eco-certifiers have also responded to shifts to the use of more plant ingredients in fish feed by including eco-certification criteria related to the responsible sourcing of land-based ingredients, sometimes relying on other certifiers like the Roundtable for Responsible Soy.

Despite advances in fish feed, many challenges to the sustainable future of the blue revolution persist; parasites, climate change, and the local social and economic impacts of aquaculture require ongoing attention. Advances in technology and regulation will be required to address these issues. Perhaps eco-certification will also contribute to ongoing improvements in these areas, supporting the future sustainability of the blue revolution.