Metaphors have great persuasive power. They often convey a new idea, how we should feel about it, and what we should do about it. For example, when crime is framed as a beast, people are more likely to view enforcement-oriented approaches as a solution. Whereas, when crime is framed as a virus, people are more likely to endorse solutions framed as a cure. So what happens when we use two different metaphors to frame the same idea?

Mixing metaphors is often considered a language ‘faux pas’ that can lead to unnecessary confusion. A mixed metaphor is a metaphor that combines two inconsistent or incongruous framings. For example, consider the mixed metaphor “we will need to iron out the bottlenecks”. This metaphor mixes framing the issue as a wrinkle that can be smoothed out through ironing, and a bottleneck that disrupts the flow. This doesn’t create a very clear picture of what’s happening.

Mixing metaphors can also occur if two different metaphors are used to describe the same thing. For example, if “The outcome weighed heavily on his shoulders,” is followed by, “He swallowed that burden and pushed on,” two different frames of reference are used to understand the same thing. When two different metaphors are used like this to describe the same thing, how does this affect their persuasive power?

Some people have suggested that mixing metaphors has the potential to decrease their bias. The thought is that having multiple ways to frame the same idea decreases the bias that comes from it always being framed the same way. If crime can be a virus, or a beast, then both a cure and enforcement would be equally likely solutions. However, this is not necessarily the case.

Metaphors can mix in ways that compound and work together to produce new meanings that may carry their own bias. This is especially true when metaphors combine to produce a single image. For example, analysis of speeches announcing the completion of the Human Genome Project found that metaphors framing the genome as a ‘map’, science as a ‘voyage’, and the accomplishments of the genome project as revealing ‘new frontiers’, worked together to create imagery evoking colonial conquest and Manifest Destiny, where mapping equates to ownership and control. The idea of the government owning and controlling the genome for their own interests was seen as problematic by many groups.

In addition, Human Genome Project metaphors that framed the genome as an instruction book, and DNA as both language and code, were mixed together. These then created imagery of the genome as containing the language and instructions for human creation that had been de-coded for scientists to use. Many found this problematic for the power it granted scientists and scientific institutions who then had the unique key-code to re-design humans.

In both of these cases, metaphors that were seemingly mixed and contradictory worked together to produce imagery that had strong persuasive effects. Rather than leave open the possibility for many interpretations, the metaphors became part of larger metaphor systems that reflected broader social narratives: colonial conquest and scientific power. This in turn influenced what implications of the project concerned different groups and what policies were implemented to keep these implications in check.

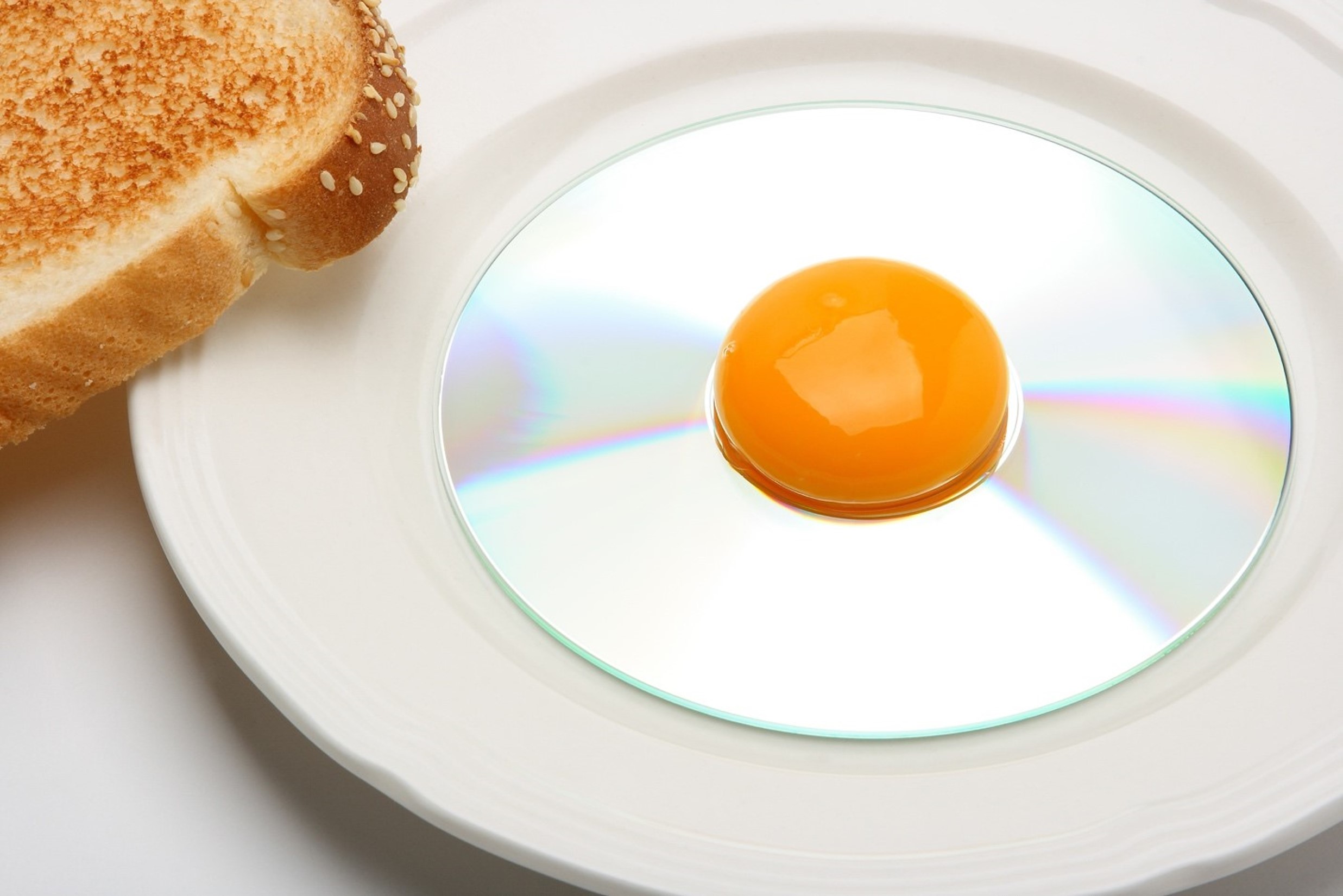

While mixed metaphors have the potential to ignite confusing by overflowing into each other’s stories, they also have the potential to re-draw the story in ways that build on existing narratives and imagery. This may not create the diversity of possible interpretations intended by using multiple metaphors. If crime is both a virus and a beast, it may become a rabid animal. If DNA is both instructions and language, we open the possibility for re-writing creation. If an idea is both deep and branching, it may instead take root. Mixing metaphors may therefore offer more clarity than obscurity – but we need to question whether together the metaphors create the lens that we intend.

Image: Chepe Nicoli via Unsplash