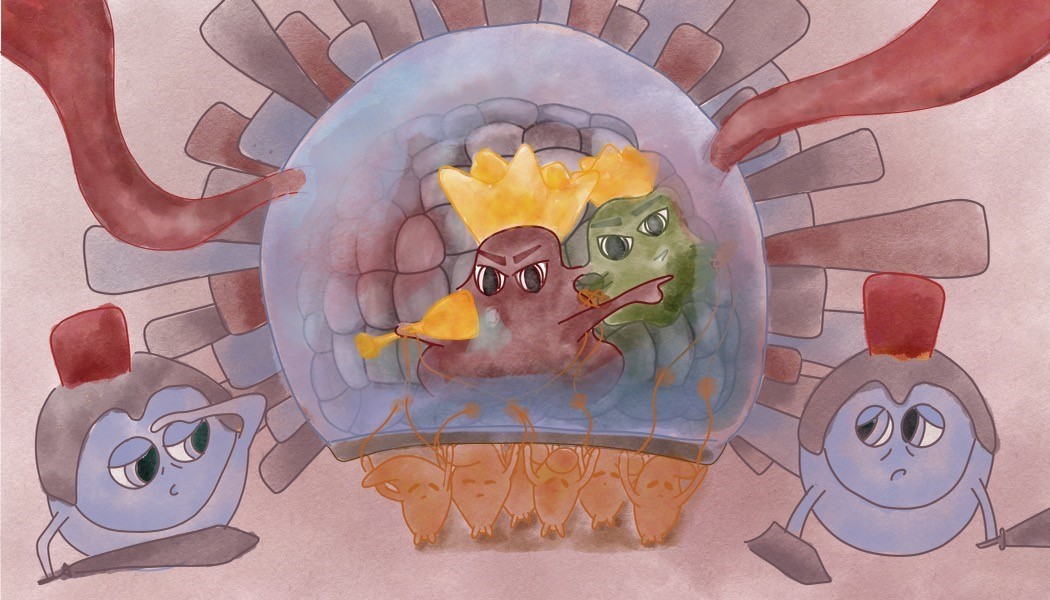

Cancer is so frequently associated with death it’s easy to forget that one of its main defining features is a relentless hunger for life. Cancer cells themselves are only one part of a tumour. In the secret life of cancer, the tumour is the kingdom where it rules from the shadows.

Hidden cancer cells sloppily drink from the fountain of youth through mutations in DNA that permit unstoppable growth or replicative immortality. Each rushed division spawns more adaptive rulers, ready for whatever challenges their kingdom might face.

In a tumour, cancer cells pirate local “citizens” – cells called fibroblasts – and demand the creation of infrastructure to expand their kingdom. With growing energy demands, cancer creates blood vessels: the roads delivering nutrients. All these sudden changes create inflammation: a signal that something bad is happening. Immune cells are recruited as the body’s warriors – prepared to repair injuries and fight infection, but cancer is self, so it’s disguised. Immune cells fill the streets of “tumour city” exhausted from cancer’s tricks.

Cancers can outgrow their primary kingdom, and so they send explorers to colonize distal sites in the body. These new settlements are tumours in the making, they can take advantage of the new surrounding resources. Timing is up to the explorers that might grow new kingdoms but they can also wait for the right time or environment to build.

Cancer treatments are weapons against these kingdoms and their thirsty rulers. Surgery directly wipes out the largest neighbourhoods by cutting them out of the body. Chemotherapy poisons cancer making it impossible to replicate and expand. Radiation mutates DNA so the only remaining fate is death. Anti-angiogenics burst blood vessels to cut off cancers energy supply. Yet, even when combined, these treatments often fail when faced with something clever, creative and inherently prepared to resist.

Cancer is alive, dynamic and adaptable; classical anti-cancer treatments are not. It’s time that we develop treatment approaches that are equally agile and durable.

Immunotherapies provide this opportunity. Our immune system is designed to detect and eliminate foreign invaders – like viruses, parasites and harmful bacteria. To mount an effective response, immune cells need to engage with their targets. Cancer, however, is an invader made up of self cells and it is also very talented at disguising itself as non-threatening.

Like many scientific findings, anti-cancer immunity was discovered accidentally. For example, in the late 1800s, cancer patients were infected with bacteria called Coley’s toxins and seemingly miraculously their cancer regressed. Then in the 1900s when we actually began treating cancer patients with radiation at a primary tumour, cancer that had metastasized to other locations also regressed. The biology behind both these miracles was in fact our immune system. Since then, we’ve discovered that many of the classical anti-cancer approaches have relied on the immune system for success. Many chemotherapies for example can induce a type of cell death that bursts open cancer cells for the immune system to inspect and respond to. Immunotherapies are more directly attempting to bolster the immune system by equipping anti-cancer cells with new methods to detect and fight cancer.

It’s here where we find immunotherapy research currently – experimenting with how we can elevate our immunity to uncover and dismantle the secret life of cancer. Taking our cues from cancer itself, and the immune system’s exquisite abilities for responsiveness, we’re training an army to overthrow the unwanted dictator.

Comic Illustration by Sarah Nersesian