You’ve probably heard the saying “An apple a day keeps the doctor away”. In reality, eating an apple a day won’t guarantee fewer trips to the doctor, but apples are still nutritious and an important part of diets globally. The nutrition provided by apples is in part due to high levels of phenolic compounds. Phenolic compounds are a large group of compounds with demonstrated antioxidant capabilities that can help reduce the risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Apples are a significant source of these nutritious compounds and some studies have shown that apples supply over 20% of the phenolic compounds consumed by North Americans.

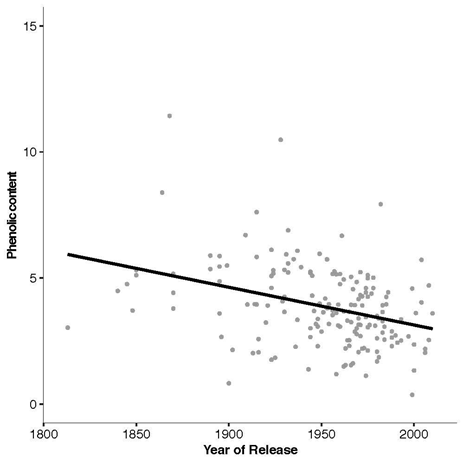

Our lab’s recent study found that phenolic content has decreased significantly over the last 200 years of apple breeding. In fact, apples that were developed prior to 1940 had 30% higher phenolic content than apples developed after 1940.

From the 1800s to present day, phenolic content has steadily declined in new apple cultivars.

You may be familiar with the browning that occurs when you cut an apple and leave it out to sit. This browning process is spurred on by high levels of phenolic compounds and many people find the appearance undesirable. Reduced browning is a trait that has been targeted by apple breeders and one of the only genetically modified apples, the Arctic apple, was developed to be non-browning.

Phenolic compounds are also responsible for imparting bitterness to apples. People tend to dislike apples with a bitter taste, unless of course the apple is being used to make cider. Within the cider industry bitterness is considered favourable as it contributes to the characteristic flavours of a cider. Within the same study by our group, we found that on average, apples used for cider tend to have higher phenolic content than apples intended for fresh consumption.

We have a hunch that in an effort to make apples brown less and taste less bitter, we may have inadvertently been reducing phenolic content. This explanation demonstrates a “double-edged sword” of plant breeding whereby a tradeoff is made because two traits are tightly linked. Phenolic compounds provide a nutritious boost to apples but come at the cost of unfavourable bitterness and browning. There are examples of breeders and food processors attempting to reduce bitterness in other crops as well. One example is with brussel sprouts where it’s thought that Dutch breeders in the 90s bred for reduced bitterness to make brussel sprouts more palatable.

Increasing phenolic content to boost nutrition may seem like a great idea in principle, but if we aren’t careful to ensure that those apples are still tasty it is unlikely that people would want to eat them. It’s hoped that with a better understanding of bitterness, browning and phenolic content we can use new genomic tools to develop apples that strike the perfect balance. To ensure the age old saying “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” still rings true, we need to breed apples that taste delicious and do not forfeit nutrition.