Note: This article was co-written by Sarah Nersesian and Morgan Pugh-Toole

High-grade serous carcinomas (HGSC) are the most deadly “ovarian” tumours. Although they can develop with signs and symptoms, most are vague, like bloating. Therefore, most individuals diagnosed with HGSC are diagnosed when cancer has already spread through the body. Unfortunately, while other cancers are seeing improved outcomes and survival thanks to technological advances, genetics and immunotherapy, HGSC survival hasn’t similarly benefited. Furthermore, HGSC outcomes haven’t changed in the past 30 years (when a specific type of chemotherapy, platinum-based, was introduced).

What is the current treatment for HGSC?

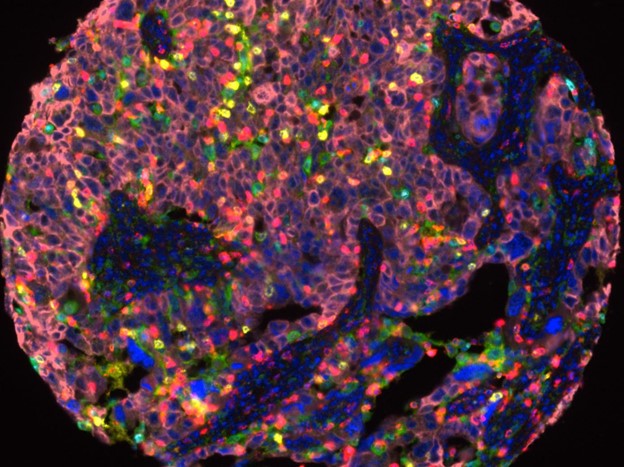

Traditional anti-cancer treatments include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. HGSC treatment usually consists of the last two. Surgery on these tumours is usually the first step in the treatment pipeline and is highly challenging. As HGSC cells spread throughout the abdominal cavity, they seed additional tumours. These tumours create their own “microenvironments,” unique features of the tumour and surrounding cells/tissues that influence how they respond to treatment. While initial surgery aims to remove as much of the tumour as possible, it frequently leaves behind several of these smaller metastatic lesions. A combination of toxic chemotherapies follows surgery to try to eliminate the rest of HGSC. These chemotherapies usually work for a short period, but eventually, the tumour develops resistance, usually through the growth of a specific tumour cell subset resistant to the therapy. Once patients reach this point, there are few options left. Secondary treatments mainly focus on prolonging life.

Why is HGSC so hard to treat?

HGSC poses numerous challenges to traditional anti-cancer treatments, and novel therapies fail in HGSC. Each patient has multiple tumours, so finding a target is impossible; imagine treating 10 cancers in a person at once. Additionally, HGSC has many strategies to evade the immune system. For example, they express proteins that tell the immune system to shut down but also shut down the process that identifies them as cancer in the first place (HLA processing). This also occurs in an environment set up to help the tumours thrive and put the immune system to sleep simultaneously.

How do NK cells meet these challenges?

Natural killer cells, or NK cells, are the ninjas of the immune system. Our lab recently described how NK cells are the missing link to improving HGSC treatment. We talk about how they have unique and adaptable features that other treatment strategies have not yet achieved When treating something as adaptable as HGSC, NK cells provide an equally agile opponent. While most immune cells targeted through therapies require the recognition of specific tumour components, NK cells can respond to generally stressed cells. This means that NK cells are better positioned to meet HGSC heterogeneity head-on by leveraging this diversity and ability to respond to a general stressed cell.

With a tumour as complex as HGSC, it has become evident that a single treatment approach will not be enough to combat this disease. Instead, strategies that combine treatments to address the challenges encountered in treating HGSC will be critical. We believe the best approach will include methods to recruit or transfer NK cells into the tumour; this could improve immune recognition and clearance of the tumour and improve outcomes for the “silent killer” of women.

About the co-author: Morgan Pugh-Toole is a second-year MSc student at Dalhousie University who led the authoring of our recent review paper, highlighting how NK cells may be the missing link for effective HGSC treatment. She is currently developing a 3D in-vivo model to study the ovarian cancer tumour microenvironment. She will also explore the impact of an NK cell-based therapy in eradicating the disease and improving outcomes.